Why Does Netflix See my Facebook Picture?

and Other Adventures with Informed Consent in Privacy Policies

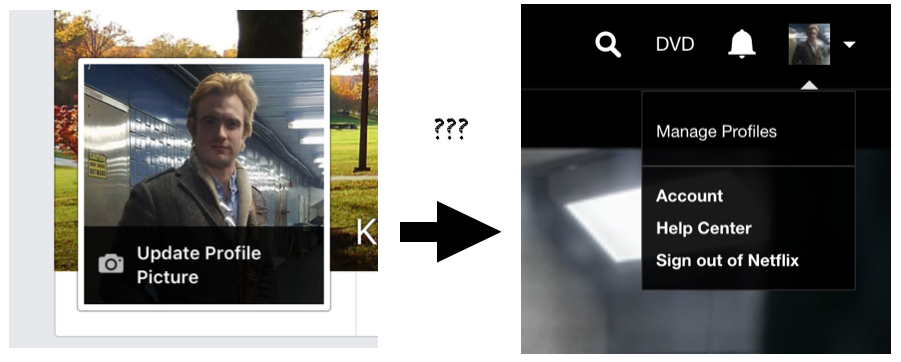

The other day I updated my Facebook profile picture. The thing I didn’t realize was that when I changed it, Netflix also got it:

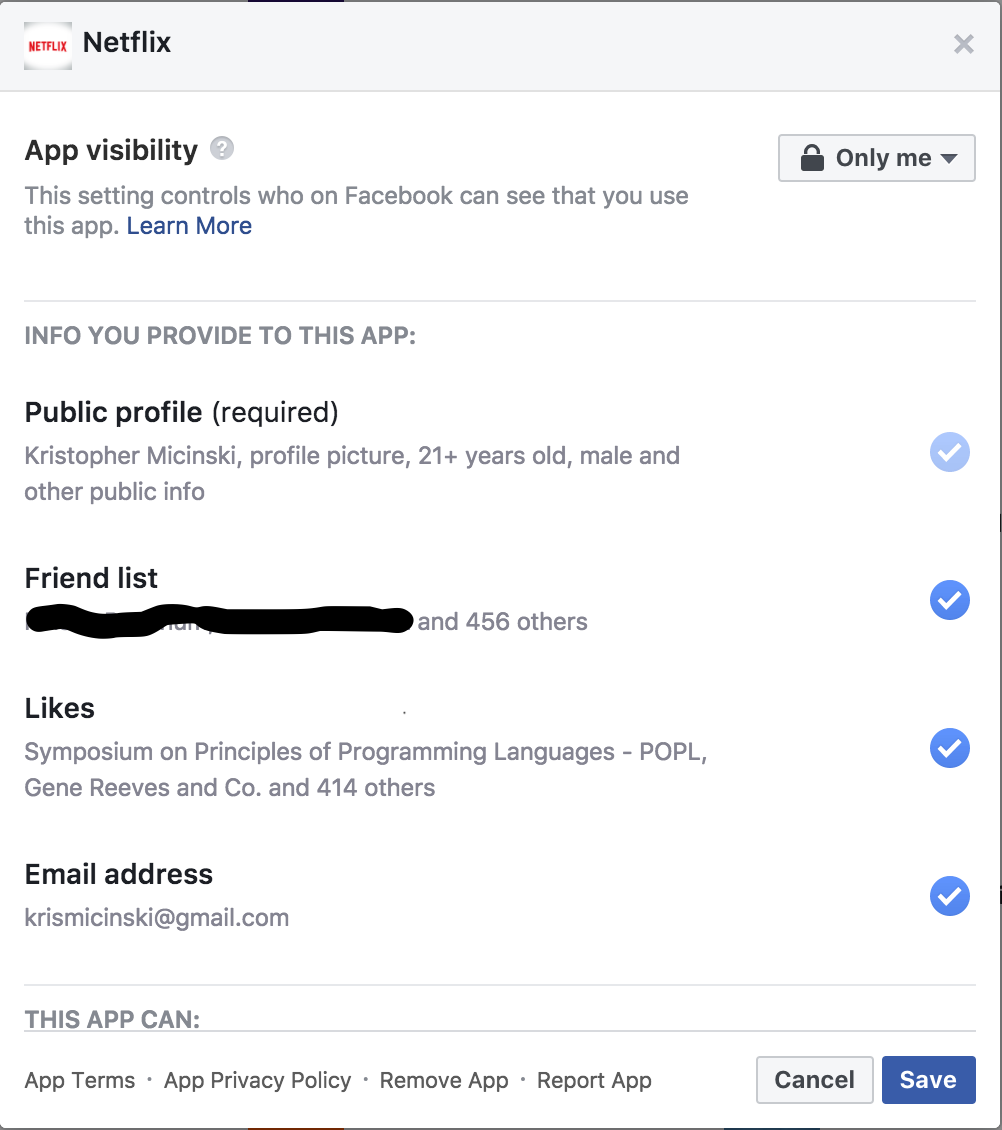

This is pretty jarring. Where was the “share this with Netflix” button that I pressed? Of course, the answer is that it’s right here:

It’s buried right there under “Public profile (required).” But there’s also a lot of other stuff I gave it access to too, I guess I forgot about that.

But why does it need access to my Facebook account at all? I just wanted to use Facebook so that I wouldn’t have to login to Netflix using an email. It’s so easy to just click in with my Facebook account, it’s everywhere!

The answer, of course, is twofold: Netflix wants to give me a more personalized experience (so they can beat out other video services) and because they want to filter it into giant machine learning algorithms to sell me ads and learn stuff about me.

So I knew all of that, but I still didn’t stop and think about Netflix getting my new profile picture whenever I changed it. Wow. I wonder what else does that!

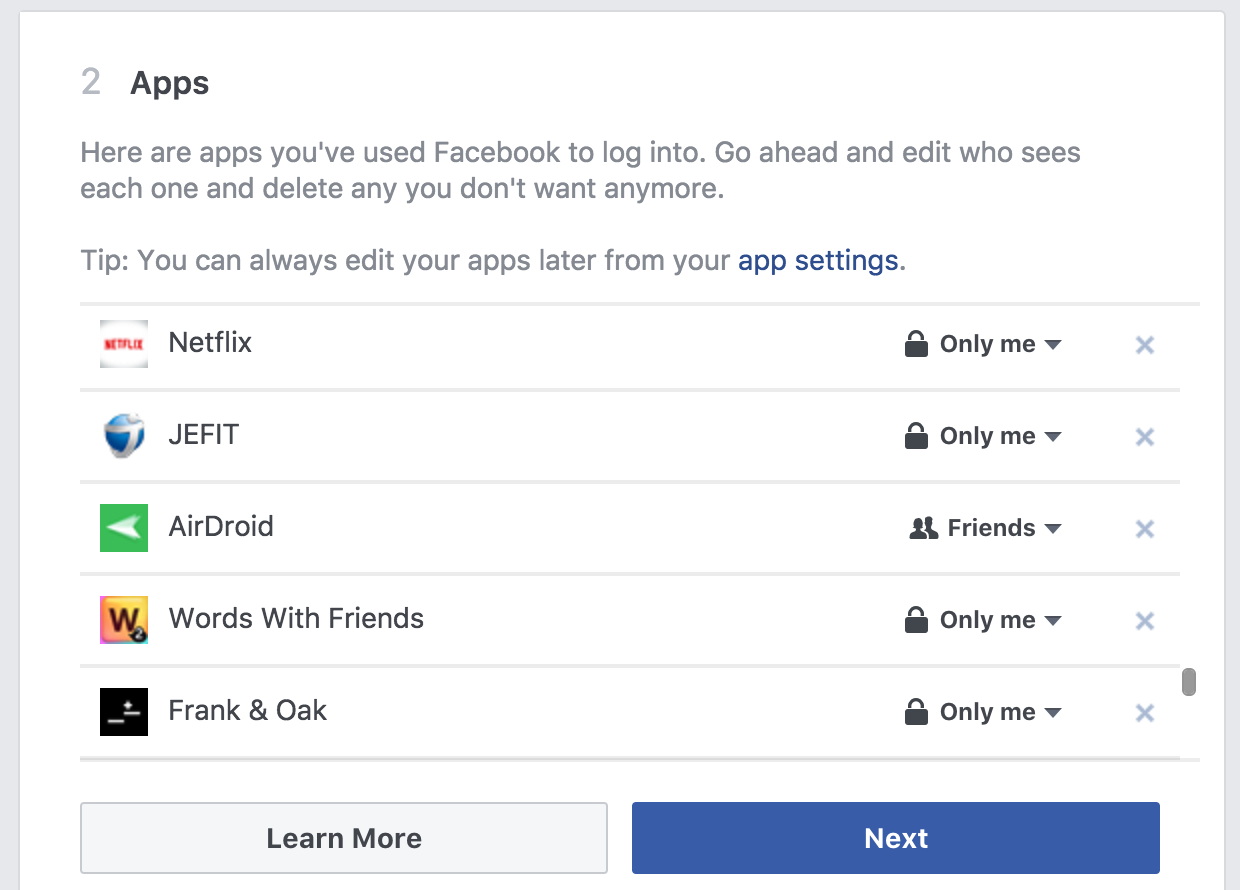

Turns out it’s hundreds of things! Facebook even has a tool for this, called their “Privacy Checkup”:

This is useful for helping you audit which apps have access to do things like post on your feed and things like that. But it doesn’t show you more nuanced things.

Here’s the big problem with all of this:

There’s a gap between what Netflix is actually using, and what I think it needs.

When I think about Netflix using my Facebook, I think it’s just because I’m logging on. But what I don’t see is that Netflix is using so much more! It’s connecting me with my friends, looking at my likes, and using that information to improve my experience.

And what’s more, Netflix probably thinks that it’s okay to do this, because after all, I agreed to it! And to be honest, they’re not totally wrong.

But I build my mental model of what Netflix is accessing based on what I see it doing, not the policy that I have to go read in a dark corner of Facebook’s privacy section (no offense to Facebook).

Background Uses Are Tricky

I contend that the main problem here is that humans are very poor at envisioning how apps will use our information in the “background.” The background is a hazy thing, but by the background I basically mean, “during a time at which I haven’t directly instructed the app to use my information by an explicit interaction (e.g., pressing a button)”

Humans are very good at understanding that their information will be used after taking some direct action. For example, after I click “share location” it’s extremely obvious that my location will be used. But we’re really bad at predicting (or remembering) what might happen when it’s been six months since we installed the app.

Here’s another example I noticed just today. I added some new contacts to the phone book on my iPhone. Later, I went to use Skype. I’m not a big fan of Skype: every other week it seems like someone’s Skype account has been hacked, so I can’t say I have a huge amount of trust in it. Of course, when Skype installed it basically forced me to allow it to access my contacts. Okay, that seems sensible, so I let it. But I didn’t realize that it would constantly get my contacts whenever I changed them. I allowed access, of course, but I didn’t really “see” Skype accessing my contacts, so why would I be surprised.

We found the same result in my CHI ‘17 paper, where we measured user expectations of permission usage within a set of vignette Android apps. Users were overwhelmingly more likely to expect access to permissions after they took a direct action, but were much less likely to expect that data was being accessed when that data was used in the background. (I’ll be giving this talk again at PrivacyCon 2018 later this year!)

And that was just for apps! Imagine how complicated it is when you’re not just on your phone, you’re using some nebulous cloud-based service. What’s worse: most apps have many different components, interact with several different APIs (Facebook, Google, Twitter, etc…), each of them using their own privacy GUIs that constantly update and change.

My frank guess is that users don’t really have any idea what’s happening until they see it. In fact, in our CHI ‘17 paper we also found that users are more likely to expect access when they see some indication of it (e.g., a banner on the top of the screen associated with the use of that permission, like a “free coffee at your local MegaCoffee” coupon). But that’s not very satisfying: what about all of the other data access they never even see?

Possible Solutions: Better Defaults, Reminders, and Audits

I’m not sure what all of the answers are, but I have a few high-level points that I take away from it:

-

Users are very poor at reasoning about data access when the access is far removed from the authorization decision.

-

They are even worse when there’s no apparent reason why the access occurs. In fact, this is almost downright malicious. Permissions are only so coarse, and while Netflix has access to a bunch of things in my “public profile”, I’d never expect it to use all of them (even though I know it does).

-

We should educate users on how / why background uses occur, and explain their relevance to app behavior if possible.

-

When we’re using coarse permissions, like “Public Profile”, we should realize that users will only expect a subset of that data to be used and act accordingly.

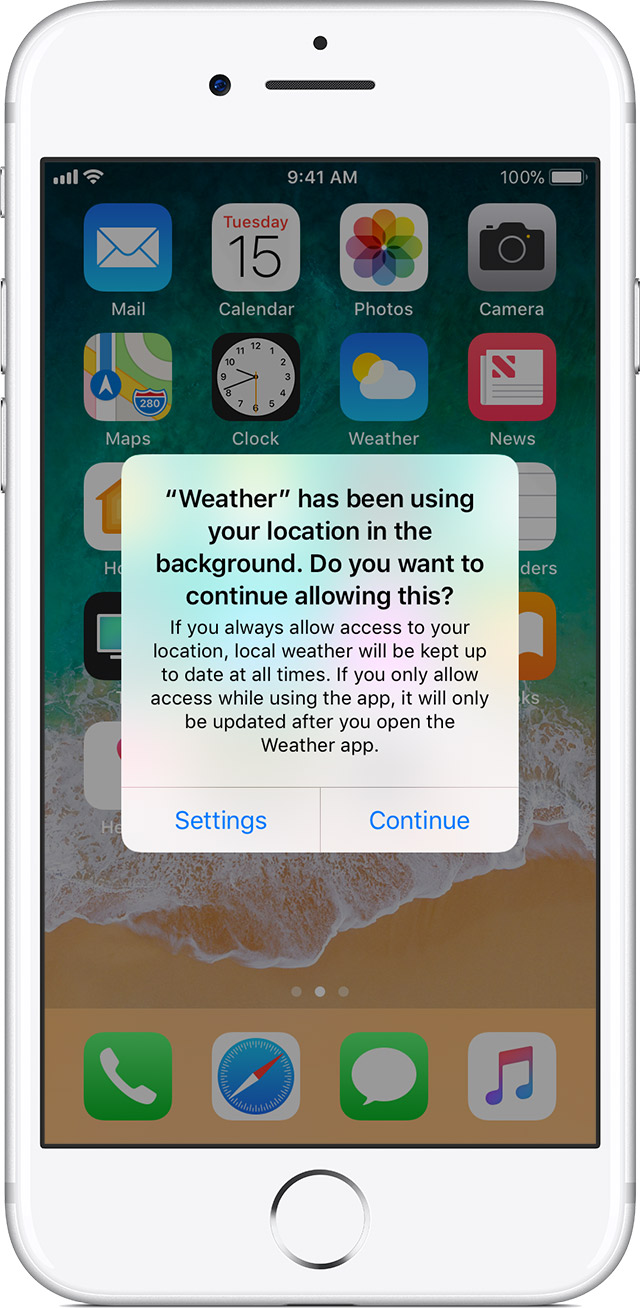

So the first thing I think we can do is better defaults. For example, Apple seems to have taken this hint. Apps can now simply request data never and “when in use”. This is a pretty intuitive thing, since users are pretty poor at conceptualizing the computational models of apps. They also go a step further and show you this nice dialog when apps have been using data in the background (I’m honestly not sure how this occurs on iOS these days):

This is nice because it helps the user “audit” which apps have been using their data. In our paper, we found that one concrete way to help users understand background usage on Android was to ask for permission right on startup before any other app functionality appeared. My hypothesis is that users said “well the app hasn’t done anything yet, so it must just need this all the time.” Still, I think that’s not a very good compromise: users will tend to associate that the information is only being used when the app appears to be using it. So we should really confine data access to when users can observe it happening.

Another concrete way I see this improving is better auditing tools to help users understand where their data will go. For example, I could imagine implementing a tool that goes through your various social networks and plays something like 20-questions with you: “do you know that when you change your Facebook picture your FindMeSingles apps is going to see it?” or something of the like. We’d need to do research to help understand the best examples to present, but I think this would be a cool idea since users reason well about examples and bad about very general policies.

A few research-y things I’m working on right now address this in a few ways:

-

Using dynamic analysis to measure when social media permissions are being used in apps. We’re in the early stages of this (still scraping apps from Google Play, let me know if you know of a better way / a good way to get a bunch of apps!), but I think this will provide some good ground truth on how apps are using these social media permissions. Of course, there are limitations here. For example, apps could pair with a web service to do the dirty work, but I think this is a good first step.

-

Log-guided program analysis that helps analysts understand why apps use permissions. Our tools use relatively cheap tricks to enable (unsound) program analyses to scale to very large apps (Bumble, Tinder, Slack) and precisely explain why permissions are used. We do this by using logs from those programs to guide the analysis.

-

Analysis-based support for lowering the performance overhead of dynamic information-flow analyses. Since many web systems are written using dynamic languages (e.g., Python), I’m excited about the possibilities of using off-the-shelf tools (like Jeeves) to specify information-flow policies that connect up to the GUI in a principled way (similar to what I did in my ESORICS ‘15 paper). The problem with these systems is that they do induce some runtime overhead, but we’re hoping to eliminate much of that by using intelligent program analysis techniques.

Longer-term, I’m interested in driving my research to understand how users conceptualize these permissions. What does that say about how we can visualize and enforce them? I’m specifically interested in cross-app policies: where the data goes from the camera app on your phone, to Instagram, to your friend’s parents after your friend clicks “like” on the image (and their parents then see it in their feed). These decisions are nuanced, and seem especially hard to explain to users. But as we have more and more apps, I think getting a handle on these things will be essential. And once we do that, we can (hopefully) start using cool language-based techniques to help enforce these policies!